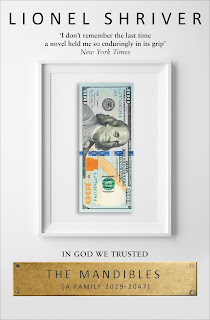

The Mandibles - Lionel Shriver

Initially then, Lionel Shriver's contribution to this growing genre of apocalyptic science-fiction isn't able to readily engage the reader's involvement, but in a way this matches the trajectory as the novel follows in the fortunes - or the loss of fortunes - of the Mandible family over the years of the great American crash from 2029 to 2047. Initially there's frustration and denial, an awful lot of hand-wringing, blaming and scapegoating. Accordingly, it doesn't make great reading at first and even Lionel Shriver's characters admit that no-one is going to be interested in "whining and carping and hand-wringing from a bunch of spoiled affluent white folks". You're not wrong there.

There's a lot of speculative but plausible and well-researched economic theory in the early part of the novel but it feels shoe-horned unnaturally into every conversation. The Mandibles are a pretty obnoxious bunch who expound at length on the circumstances that have seen their fortune and inheritance dwindle as the American dollar devalues in 2029 - despite having rallied a little after the near-collapse of 2024. It's hard to care (and that's probably the intention) when the Mandible children bemoan what has happened to their expected inheritance, or when their precocious offspring balk at the loss of their privileged lifestyles, educational opportunities and the ability to obtain expensive imported delicatessen. How will they survive without Japanese rice vinegar and bluefin tuna? Oh, the inhumanity! One thing is for sure, as everyone downsizes and the kids' colleges are reappraised, the cases of expensive wine will probably be the last thing to go.

It's funny because it's probably true that humanity will grasp to the little luxuries they believe they've worked so hard to acquire. Schriver doesn't invite you to sympathise then, but it's not entirely a case of gleeful schadenfraude at the eventual comeuppance of those who have previously shown no care or interest whatsoever in those who have never had the same benefits or opportunities. She is judicious in her choice of mainly academic careers that the Mandibles see become an irrelevance as the demand (unsurprisingly) drops for economics professors in tenure at elite American universities.

As for writers ...well, the decline of libraries, print media and people actually buying books means that they haven't been relevant for a long time. They're not going to be much use when it comes to providing for the necessities when currency goes down the plughole. Again, if this feels like clever literary self-reflection and self-deprecation on the part of Shriver, putting economists on the same level as writers - particularly those of apocalyptic fiction - it's for a reason. No-one really takes heed of doomsayers either, and, even if they did, knowing that the truck is coming won't stop it from blindsiding you, as Great Grand Man Mandible notes at one point.

On the subject of great prophets of the apocalypse, I think J.G. Ballard would have taken a perverse pleasure wallowing in the proximity of the incipient disaster that now seems inevitable. Not from a 'told you so' doomsayer visionary point of view in the traditional sense of predicting what the future holds in store, but from what now can be recognised as his perceptive and visionary insights into psychopathological impulses of the individuals within the artificial construct of society. If the collapse of traditional social values was a constant theme with Ballard, one of which he had direct experience watching the niceties of civilised behaviour break down while in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, Ballard's writing went far beyond observation of what humans do to survive. As can be seen from the recent film version of High Rise, what Ballard observed was that the barely-concealed savagery within people that is brought out in such extreme conditions doesn't necessarily have need the stimulus of societal collapse, but rather there's an almost pathological relish at the prospect and a headlong rush to actively seek it out.

While I don't think Shriver is as daring and experimental as Ballard she is clearly brilliantly attuned to the workings of the affluent-white-American mindset (and the nature of writers) and how they will almost perversely be the willing agents of their own destruction. And, to be fair, she explores Americans' response to deprivation with a lot more obvious humour and writing flair than Ballard could ever have done. Her writing is at her best as she describes that declining state of affairs that drive the formerly rich Mandibles from denial to recognition, imagining every little deprivation suffered by them, every petty indignity, finding witty expressions and juxtapositions, almost gleefully detailing their decline in petty squabbles over luxuries versus necessities with incisive and insightful observations.

So what use is The Mandibles? Does it have any lessons to impart that might help safeguard us from the inevitable collapse of society as we know it? As witty and realistic as Shriver's account is of the failure of the capitalist system that she brilliantly terms "The American Experiment", the suspicion of it being merely a literary exercise persists. "There's a great book in this upheaval", GGM observes, "For most people, what lies outside our front door is tragedy. For Enola [his writer daughter], it's material". It's material too for Shriver is the obvious oh-so-clever implication, and she relishes the opportunity it provides to make wryly amusing observations, playing imaginatively with the language needed to describe events and situations that have yet to come to pass, but which will inevitably happen in some form or other. The implication however, as the use and manipulation of language indicates, is that the 'material' is already there, Shriver observing that the freedoms we give up to 'the system' today - to technology, to business and to the government - will influence the ease with which we submit to the inevitable tomorrow.

And if the novel seems America-centric, well there's a good reason for that too - and it's well backed up with all the economic theory. If it's the richest who are going to take the biggest hit when economic confidence fails, it will be America that is hit the hardest. As the Mandibles discover, you soon find out who your friends are when it comes down to the crunch, and as it stands, America hasn't been doing all that great at making friends around the world lately. While Shriver might indeed be getting in there just under the wire then with the Great American Disaster Novel while people still read "stained wood pulp", The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047 is not just a literary exercise in premonitory apocalyptica, it's not a gleeful demolition of the indulgences and delusions of the wealthy elite, and it's not a survivalist exploration of the human capacity to adapt and rebuild. Well, it is all those things and the post-capitalism/post-American/post-economy landscape that Shriver goes on to depict is an interesting one, but hopefully there's a bit more to the novel than that too.

You might not particularly care about how the various members of the über-rich Mandible family cope, and you might not agree that Shriver's reading of the outcome of the direction we are all heading in the future is a plausible one, but The Mandibles is not just a literary exercise in a growing genre of disaster fiction. Like the best science-fiction Shriver's latest novel ought to give the reader pause to consider that we choices we make today will determine the kind of future we deserve tomorrow.

The Mandibles: A Family, 2029-2047 by Lionel Shriver is published by Harper on 21 Jun 2016

Comments

Post a Comment